Riding the Waves with David and Goliath: Venerable Big Pharma and the Plucky Little Biotech

Posted By Jon Lavietes, Monday, October 5, 2020

The ASAP biopharma community is no stranger to big pharma–biotech alliances and David-Goliath partnerships. In general, the story usually centers around an entity with an intriguing molecule accompanied by promising science looking for a partner with deep expertise—and pockets—to help develop the therapeutic candidate into a viable alternative for doctors to prescribe.

Little Biotech Grows Up

But what happens if that ambitious young company eventually wants more? Does its larger ally accommodate its growth and evolution, or is it a sign that the two partners have grown apart? The answer depends on the collaboration—as the old axiom that has been bandied about in ASAP circles seemingly forever goes, “If you’ve seen one alliance, then you’ve seen one alliance.”

On demand now to attendees of the 2020 ASAP BioPharma Conference is the story of one David-Goliath collaboration that successfully navigated—and adjusted to—the little sibling growing up. The session “The Evolution Highs and Lows of a Biotech and Pharma Alliance” shares how the venerable 352-year-old Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany and 13-year-old F-star Therapeutics first started working together in 2011 to explore the latter’s ability to make antibodies and ultimately evolved their collaboration into a complex M&A licensing arrangement in part due to F-star’s transformation from an R&D–focused company to one with bets on a wholly owned portfolio.

Senior Leaders Are a Couple of Blocks Short of Reaching Alliance Heights

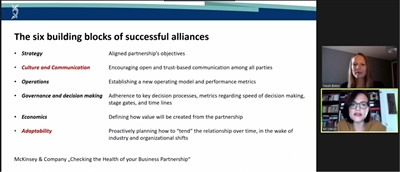

Margarita Wucherer-Plietker, CA-AM, director of alliance management at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, began the story by listing six building blocks of alliances as defined by McKinsey:

- Strategy – Alignment of partnership objectives

- Culture and communication – Open and trust-based communication among all parties

- Operations – The establishment of a new operating model and performance metrics

- Governance/decision making – Adherence to key decision processes, and metrics for speed of decision making, stage gates, and timelines

- Economics – Defining how much value will be created by the partnership

- Adaptability – Proactive planning of how to tend to the relationship over time in the wake of industry and organizational shifts

She said that, according to McKinsey, executives tended to be aware of the importance of strategy, governance, and decision-making processes—parts of the organizational machine that C-suite executives are steeped in regularly—to driving alliance success. However, they also had a proclivity to undervalue intangible factors like culture and communication, as well as adaptability. Guess which of these cornerstones proved to be more valuable to Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, and F-star? (Spoiler alert: senior leaders have it all wrong!)

Data-Driven Mindset Fuels Alliance Growth

When Sarah Batey, PhD, vice president of project and portfolio management at F-star Therapeutics, started at F-star in 2011, the collaboration was in its infancy with small teams of scientists working with a standard licensing agreement. The parties gelled quickly, finding that they were able to communicate openly and deliver consistently “against well-thought-out, achievable-but-still-demanding work plans.” The companies also found that they were simpatico in that each applied a “similar science and data-driven mindset” to their work, according to Batey.

The trust built over time ended up being a key factor down the road when the collaboration expanded in 2017 to include multiple assets, including the clinical candidate FS118. The collaboration expanded again in 2019 when F-star retained FS118, while Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, exercised the option for one discovery-stage program and retained the option for a second one. In 2020, the partnership would evolve again in the face of COVID-19 (more on that later) as Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, exercised another option on an immune-oncology collaboration and the companies added two more preclinical discovery programs.

Even today, “the collaboration still thrives based on the joint data-driven decision making,” said Batey, who added that the team members rarely consult the contract to resolve a situation, an example of their ability to smooth out differences.

Jiffy Lube: Seamless Execution of Governance Greases Well-Oiled Machine

How did these two organizations manage this growth? They devised a traditional model, with a Joint Steering Committee (JSC) overseeing Joint Project Teams (JPTs) for preclinical and clinical assets. It would turn out that nothing more intricate was needed because all stakeholders put in the necessary work to make the governance mechanisms function like a well-oiled machine. The senior leaders from both companies who sat on the JSC were well versed on the alliance’s mission and value propositions, and they made themselves readily available for critical discussions. The JPTs were made up of passionate scientists who deftly organized communications and project workflows. They would prepare detailed presentations at appropriate junctures for JSC meetings in order to thoroughly brief the leadership team ahead of moments when critical decisions needed to be made. (This seamless flow of communication between the JPTs and JSC stands in stark contrast to an alliance presented in another BioPharma Conference session that initially struggled to manage what information got delivered to its top committee.)

That isn’t to say that they didn’t have to make adjustments. The smaller F-star wasn’t accustomed to working with larger bureaucratic structures, so the companies agreed to prioritize stage-gate decision-making moments and make sure that alignment was achieved on important details.

On an operational level, alliance managers served as a “central point,” to whom project managers and leads would reach out whenever there was a question about budget, messaging, timelines, or another key element of the alliance, according to Wucherer-Plietker. Alliance managers proved to be effective gatekeepers, as they were able to efficiently facilitate engagement with business development, legal, IP, and other functions whenever they needed to be consulted.

“The key learning here is that a clearly defined touchpoint—a presence in the teams—between all parties and the central touchpoint, alliance management, was very helpful for this alliance to bring projects forward,” said Wucherer-Plietker, who pointed out that the importance of this communication flow contradicted senior management’s underestimation of this building block, as detailed in McKinsey’s findings.

Stormy Weather and a Sea Change

This streamlined operation helped the collaboration sail through what Batey called “stormy waters” over the last several years.

“Even best laid plans can’t necessarily predict every future eventuality,” she reminded viewers.

The alliance has endured waves created by the departure of key personnel, including champions of the collaboration, and F-star’s evolution from a platform company into an organization with a proprietary pipeline. When F-star was making its move, it approached its partner about obtaining increased development and commercial rights for FS118.

“Ultimately, a change in pipeline prioritization resulted in the program fully reverting back to F-star, while Merck took the rights to an alternative program,” recounted Batey. The sides were able to negotiate a mutually valuable agreement for both sides—Batey called it “the rainbow at the end of the storm.”

The alliance also experienced external turbulence, or “at-sea waves,” said Batey, continuing with the oceanic theme. Like most biopharma collaborations, it confronted changes in the competitive landscape and scientific challenges related to target validation. However, in the presentation Batey spoke mostly about the surfing competition–sized wave disrupting everyone’s sea cruise: COVID-19. The pandemic allowed the parties to take a step back and evaluate the strategy and objectives pf the partnership, as well as what was best for patients. This is when Merck took the early option on the immune-oncology collaboration and added two more.

“In both cases, we really felt that those storm waves were a key trigger to critically review the collaboration and ultimately, in the end, bask in the rainbows. This was due to the strong relationship and trust that we had built. The strong boat was able to face the waves,” said Batey.

Wucherer-Plietker boiled down how the two organizations were able to find opportunities in times of crisis to four steps:

- Both parties acknowledged and appreciated that changes in the landscape could potentially cause a divergence in the parties’ interests and viewpoints.

- They maintained open communication on common goals and diverging interests as they related to strategic and pipeline changes.

- They developed a joint view and aligned objectives vis-à-vis the divergence in their respective priorities that resulted from the crisis situation.

- This allowed the allies to put initiatives in place that would help exploit whatever points of value remained in the collaboration.

Communication, Adaptability Turn Crises into Opportunities

To conclude the panel, Wucherer-Plietker preceded a list of key takeaways with the observation that “these building blocks, communication and adaptability, should never be underestimated.” She began the list with the assertion that an alliance is unsustainable without alignment around “high-profile alliance goals.” Wucherer-Plietker added that “these goals can be built and elevated over time.” The second key to success: enthusiastic teams who collaborate closely and communicate openly, not only when times are good but also when tough conversations are necessary. Next, trust, as always, is essential in an alliance. Wucherer-Plietker listed three ways to build it in the pharma context: 1) reliably deliver targets, 2) be transparent and define communications protocols at all levels, and 3) expect and appreciate change to the business and scientific environment over time. Finally, she urged viewers to view change as “an opportunity, not a crisis,” as they represent “inflection points” that could lead to new or reconfigured deals that work better for everyone.

More ASAP BioPharma Conference sessions, both prerecorded presentations and keynotes and panels from the livestream portion of the event, are available at the event’s portal, so check them out now for the latest trends and perspectives from biopharma alliance thought leaders.